Articles liés à Purgatorio

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

If a poem is not forgotten as soon as the circumstances of its origin, it begins at once to evolve an existence of its own, in minds and lives, and then even in words, that its singular maker could never have imagined. The poem that survives the receding particulars of a given age and place soon becomes a shifting kaleidoscope of perceptions, each of them in turn provisional and subject to time and change, and increasingly foreign to those horizons of human history that fostered the original images and references.

Over the years of trying to approach Dante through the words he left and some of those written about him, I have come to wonder what his very name means now, and to whom. Toward the end of the Purgatorio, in which the journey repeatedly brings the pilgrim to reunions with poets, memories and projections of poets, the recurring names of poets, Beatrice, at a moment of unfathomable loss and exposure, calls the poem's narrator and protagonist by name, "Dante," and the utterance of it is unaccountably startling and humbling. Even though it is spoken by that Beatrice who has been the sense and magnet of the whole poem and, as he has come to imagine it, of his life, and though it is heard at the top of the mountain of Purgatory, with the terrible journey done and the prospect of eternal joy ahead, the sound of his name at that moment is not at all reassuring. Would it ever be? And who would it reassure? There was, and there is, first of all, Dante the narrator. And there was Dante the man living and suffering in time, and at once we can see that there is a distinction, a division, between them. And then there was, and there is, Dante the representation of Everyman, of a brief period in the history of Italy and of Florence, of a philosophical position, a political allegiance -- the list is indeterminate. Sometimes he seems to be all of them at once, and sometimes particular aspects occupy the foreground.

The commentaries date back into his own lifetime -- indeed, he begins them himself, with the Vita Nuova -- and the exegetes recognized from the beginning, whether they approved or not, the importance of the poem, the work, the vision, as they tried to arrive at some fixed significance in those words, in a later time when the words themselves were not quite the same.

Any reader of Dante now is in debt to generations of scholars working for centuries to illuminate the unknown by means of the known. Any translator shares that enormous debt. A translation, on the other hand, is seldom likely to be of much interest to scholars, who presumably sustain themselves directly upon the inexhaustible original. A translation is made for the general reader of its own time and language, a person who, it is presumed, cannot read, or is certainly not on familiar terms with, the original, and may scarcely know it except by reputation.

It is hazardous to generalize even about the general reader, who is nobody in particular and is encountered only as an exception. But my impression is that most readers at present whose first language is English probably think of Dante as the author of one work, The Divine Comedy, of a date vaguely medieval, its subject a journey through Hell. The whole poem, for many, has come to be known by the Inferno alone, the first of the three utterly distinct sections of the work, the first of the three states of the psyche that Dante set himself to explore and portray.

There are surely many reasons for this predilection, if that is the word, for the Inferno. Some of them must come from the human sensibility's immediate recognition of perennial aspects of its own nature. In the language of modern psychology the Inferno portrays the locked, unalterable ego, form after form of it, the self and its despair forever inseparable. The terrors and pain, the absence of any hope, are the ground of the drama of the Inferno, its nightmare grip upon the reader, its awful authority, and the feeling, even among the secular, that it is depicting something in the human makeup that cannot, with real assurance, be denied. That authority, with the assistance of a succession of haunting illustrations of the Inferno, has made moments and elements of that part of the journey familiar and disturbing images which remain current even in our scattered and evanescent culture.

The literary presence of the Inferno in English has been renewed in recent years. In 1991 Daniel Halpern asked a number of contemporary poets to provide translations of cantos of the Inferno which would eventually comprise a complete translation of the first part of the Commedia. Seamus Heaney had already published fine versions of sections from several of the cantos, including part of canto 3 in Seeing Things (1991), and he ended up doing the opening cantos. When Halpern asked me to contribute to the project, I replied chiefly with misgivings, to begin with. I had been trying to read Dante, and reading about him, since I was a student, carrying one volume or another of the bilingual Temple Classics edition -- pocket-sized books -- with me wherever I went. I had read parts, at least, of the best-known translations of the Commedia: Henry Francis Cary's because it came with the Gustave Doré illustrations and was in the house when I was a child; Longfellow's despite a late-adolescent resistance to nineteenth-century poetic conventions; Laurence Binyon's at the recommendation of Ezra Pound, although he seemed to me terribly tangled; John Ciardi's toward which I had other reservations. The closer I got to feeling that I was beginning to "know" a line or a passage, having the words by memory, repeating some stumbling approximation of the sounds and cadence, pondering what I had been able to glimpse of the rings of sense, the more certain I became that -- beyond the ordinary and obvious impossibility of translating poetry or anything else -- the translation of Dante had a dimension of impossibility of its own. I had even lectured on Dante and demonstrated the impossibility of translating him, taking a single line from the introductory first canto, examining it word by word:

Tant' ê amara che poco ê più morte

indicating the sounds of the words, their primary meanings, implications in the context of the poem and in the circumstances and life of the narrator, the sound of the line insofar as I could simulate it and those present could repeat it aloud and begin to hear its disturbing mantric tone. How could that, then, really be translated? It could not, of course. It could not be anything else. It could not be the original in other words, in another language. I presented the classical objection to translation with multiplied emphasis. Translation of poetry is an enterprise that is always in certain respects impossible, and yet on occasion it has produced something new, something else, of value, and sometimes, on the other side of a sea change, it has brought up poetry again.

Halpern did not dispute my objections, but he told me which poets he was asking to contribute to the project. He asked me which cantos I would like to do if I decided to try any myself. I thought, in spite of what I had said, of the passage at the end of canto 26, where Odysseus, adrift in a two-pointed flame in the abyss of Hell, tells Virgil "where he went to die" after his return to Ithaca. Odysseus recounts his own speech to "that small company by whom I had not been deserted," exhorting them to sail with him past the horizons of the known world to the unpeopled side of the earth, in order not to live "like brutes, but in pursuit of virtue and knowledge," and of their sailing, finally, so far that they saw the summit of Mount Purgatory rising from the sea, before a wave came out from its shore and overwhelmed them. It was the passage of the Commedia that had first caught me by the hair when I was a student, and it had gone on ringing in my head as I read commentaries and essays about it, and about Dante's figure of Odysseus. Odysseus says to Virgil:

Io e i compagni eravam vecchi e tardi

In the Temple Classics edition, where I first read it, or remember first reading it, the translation by John Aitken Carlyle, originally published in 1849, reads

I and my companions were old and tardy

and it was the word "tardy" that seemed to me not quite right, from the start. While I was still a student, I read the John D. Sinclair translation (Oxford), originally published in 1939, where the words read

I and my companions were old and slow

"Slow," I realized, must have been part of the original meaning, of the intent of the phrase, but I could not believe that it was the sense that had determined its being there.

The Charles S. Singleton translation, published in 1970, a masterful piece of scholarly summary, once again says

I and my companions were old and slow

That amounts to considerable authority, and it was, after all, technically correct, the dictionary meaning, and the companions surely must have been slowed down by age when Odysseus spoke to them. But I kept the original in my mind: "tardi," the principal sense of which, in that passage, I thought had not been conveyed by any of the translations.

When I told Halpern that I would see whether I could provide anything of use to him, I thought of that word, "tardi." It had never occurred to me to try to translate it myself, and I suppose I believed that right there I would have all my reservations about translating Dante confirmed beyond further discussion. As I considered the word in that speech it seemed to me that the most important meaning of "tardi" was not "tardy," although it had taken them all many years to sail from Troy. And not "slow," despite the fact that the quickness of youth must have been diminished in them. Nor "late," which I had seen in other versions, and certainly not "late" in the sense of being late for dinner. I thought the point was that they were late in the sense that an hour of the day may be late, or a day of a season or a year or a destiny: "late" meaning not having much time left. And I considered

I and my companions were old and near the end

and how that went with what we knew of those lines, how it bore upon the lines that followed. Without realizing it I was already caught.

That canto had always been for me one of the most magnetic sections of the Inferno, and among the reasons for that was the figure of Dante's Odysseus, the voice in the flame, very far from Homer's hero, whom Dante is believed to have known only at second hand, from Virgil and other Latin classics and translations. Apparently Odysseus' final voyage is at least in part Dante's invention, and it allows him to make of Odysseus in some sense a "modern" figure, pursuing knowledge for its own sake. In Dante's own eagerness to learn about the flames floating like fireflies in the abyss he risks falling into the dark chasm himself.

That final voyage in the story of Odysseus is one of the links, within the ultimate metaphor of the poem, between the closed, immutable world of the Inferno and Mount Purgatory. It represents Odysseus' attempt to break out of the limitations of his own time and place by the exercise of intelligence and audacity alone. In the poem, Mount Purgatory had been formed out of the abyss of Hell when the fall of Lucifer hollowed out the center of the earth and the displaced earth erupted on the other side of the globe and became the great mountain, its opposite. And canto 26 of the Inferno bears several suggestive parallels to the canto of the same number in the Purgatorio. In the latter once again there is fire, a ring of it encircling the mountain, and again with spirits in the flames. This time some of the spirits whom Dante meets are poets. They refer to each other in sequence with an unqualified generosity born of love of each other's talents and accomplishments (this is where the phrase "il miglior fabbro" comes from, as one of Dante's predecessors refers to another) and their fault is love, presumably worldly love, and no doubt for its own sake. The end of that canto is one of Dante's many moving tributes to other poets and to the poetry of others. When at last he addresses the great Provençal troubadour Arnaut Daniel, the troubadour generously refers to Dante's question as "courteous" -- a word that, within decades of the great days of the troubadours and the courts of love, and then the vicious devastations of the Albigensian Crusade, evoked an entire code of behavior and view of the world. And in Dante's poem, Daniel's reply, eight lines of it that are among the most beautiful lines in the poem, is in Daniel's own Provençal, and it echoes one of Daniel's own most personal and compelling poems with an affectionate, eloquent closeness like that of Mozart's quartets dedicated to Haydn.

The Commedia must be one of the most carefully planned poems ever written. Everything in it seems to have been thought out beforehand, and yet such is the integrity of Dante's gift that the intricate consistency of the design is finally inseparable from the passion of the narrative and the power of the poetry. His interest in numerology, as in virtually every other field of thought or speculation in his time, was clearly part of the design at every other point, and the burning in the two cantos numbered twenty-six is unlikely to have come about without numerological consideration. His own evident attraction to the conditions of the soul, the "faults," in each canto, is a further connection.

The link between the Odysseus passage and Mount Purgatory was one of the things that impelled me to go on trying to translate that canto for Halpern's project. (I eventually sent him the result, along with a translation of the following canto.) Those two cantos which I contributed to his proposed Inferno I include here even though Robert Pinsky has since published his own translation of the whole of the Inferno -- a clear, powerful, masterful gift not only to Dante translation in our language but to the poetry of our time. I am beginning with my own translations of these cantos partly because they are where I started, and because they provide the first glimpse in the poem of Mount Purgatory, seen only once, at a great distance, and fatally, at the end of the mortal life of someone who was trying to break out of the laws of creation of Dante's moral universe

For in the years of my reading Dante, after the first overwhelming, reverberating spell of the Inferno, which I think never leaves one afterward, it was the Purgatorio that I had found myself returning to with a different, deepening attachment, until I reached a point when it was never far from me; I always had a copy within reach, and often seemed to be trying to recall part of a line, like some half-remembered song. One of the wonders of the Commedia is that, within its single coherent vision, each of the three sections is distinct, even to the sensibility, the tone, the feeling of existence. The difference begins at once in the Purgatorio, after the opening lines of invocation where Dante addresses the holy Muses (associated with their own Mount Helicon) to ask that poetry rise from the dead -- literally, "dead poetry [la morta poesì] rise up again." Suddenly there is the word "dolce" -- sweet, tender, or all that is to be desired in that word in Italian and in the word's siblings in Provençal and French -- and then "color," and there has been nothing like that before. Where are we?

We -- the reader on this pilgrimage, with the narrator and h...

Allen Mendelbaum's five verse volumes are: Chelmaxions; The Savantasse of Montparnasse; Journeyman; Leaves of Absence; and A Lied of Letterpress. His volumes of verse translation include The Aeneid of Virgil, a University of California Press volume (now available from Bantam) for which he won a National Book Award; the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso volumes of the California Dante (now available from Bantam); The Odyssey of Homer (now available from Bantam); The Metamorphoses of Ovid, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in poetry; Ovid in Sicily; Selected Poems of Giuseppe Ungaretti; Selected Writings of Salvatore Quasimodo; and David Maria Turoldo. Mandelbaum is co-editor with Robert Richardson Jr. of Three Centuries of American Poetry (Bantam Books) and, with Yehuda Amichai, of the eight volumes of the JPS Jewish Poetry Series. After receiving his Ph.D. from Columbia, he was in the Society of Fellows at Harvard. While chairman of the Ph.D. program in English at the Graduate Center of CUNY, he was a visiting professor at Washington University in St. Louis, and at the universities of Houston, Denver, Colorado, and Purdue. His honorary degrees are from Notre Dame University, Purdue University, the University of Assino, and the University of Torino. He received the Gold Medal of Honor from the city of Florence in 2000, celebrating the 735th anniversary of Dante's birth, the only translator to be so honored; and in 2003 he received the President of Italy's award for translation. He is now Professor of the History of Literary Criticism at the University of Turin and the W.R. Kenan Professor of Humanities at Wake Forest University.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

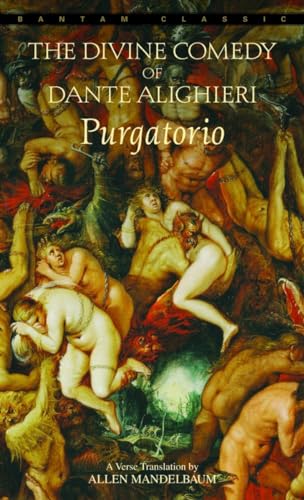

- ÉditeurBantam Classics

- Date d'édition1983

- ISBN 10 055321344X

- ISBN 13 9780553213447

- ReliurePoche

- Nombre de pages448

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

Gratuit

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Purgatorio (Bantam Classics) by Dante Alighieri [Mass Market Paperback ]

Description du livre Soft Cover. Etat : new. Barry Moser (illustrateur). N° de réf. du vendeur 9780553213447

Purgatorio

Description du livre Pocket Books. Etat : New. Barry Moser (illustrateur). Publisher overstock, may contain remainder mark on edge. N° de réf. du vendeur 9780553213447B

Purgatorio (Bantam Classics) [Mass Market Paperback] Dante Alighieri; Barry Moser and Allen Mandelbaum

Description du livre Etat : New. Barry Moser (illustrateur). Brand New! Not Overstocks or Low Quality Book Club Editions! Direct From the Publisher! We're not a giant, faceless warehouse organization! We're a small town bookstore that loves books and loves it's customers! Buy from Lakeside Books!. N° de réf. du vendeur OTF-S-9780553213447

Purgatorio (Paperback or Softback)

Description du livre Paperback or Softback. Etat : New. Barry Moser (illustrateur). Purgatorio 0.45. Book. N° de réf. du vendeur BBS-9780553213447

Purgatorio : The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri

Description du livre Etat : New. Barry Moser (illustrateur). N° de réf. du vendeur 430625-n

Purgatorio (Bantam Classics)

Description du livre Etat : New. Barry Moser (illustrateur). Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition 0.5. N° de réf. du vendeur bk055321344Xxvz189zvxnew

Purgatorio (Bantam Classics)

Description du livre Etat : New. Barry Moser (illustrateur). New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.5. N° de réf. du vendeur 353-055321344X-new

Purgatorio (Bantam Classics)

Description du livre Mass Market Paperback. Etat : New. Barry Moser (illustrateur). Brand New!. N° de réf. du vendeur 055321344X

Purgatorio (Bantam Classics)

Description du livre Etat : New. Barry Moser (illustrateur). . N° de réf. du vendeur 52GZZZ00DDV0_ns

Purgatorio (Bantam Classics)

Description du livre Etat : New. Barry Moser (illustrateur). N° de réf. du vendeur I-9780553213447